I was having a conversation with our Kung-Fu instructor, Sifu Chik Mason, about how fortunate I thought he was to be able to return to the dojo not even a week after having two brain surgeries. He was diagnosed with a hematoma and needed emergency surgery. His recovery was remarkable and he attributed his physical resilience to his martial art training. In the same conversation we went on to lament the loss of his abilities that he had when he was younger. He is now 75 years old.

We went deep into a conversation that can be summarized as about the TAO and the tension between the glory of a top level practitioner and the lackluster perception of prioritizing longevity for your practice. I mention the TAO because all things have a way about them that is in accordance with their natural process. For example, a seed will naturally grow sprouts and roots on its own. It is what a seed does naturally. Stems grow upwards and roots grow downwards; that is the TAO of roots and stems.

Human life also has a TAO. You are born a baby, become an infant, toddler, early learner, school age child, adolescent, young adult, and then a mature adult; it is the TAO of life being human. When you reflect across a lifespan of practice there are phases that align with this. First you develop your capacities or potential. From birth through being a young adult we can enjoy the greatest gains. After this we are in the “use and testing” phase of our potential. This phase is generally aligned with adolescence and young adulthood. This is what I call the glory phase of a practitioner’s life cycle. The time spent in this phase can range from 16 years old to approximately the late thirties, maybe forty years old. Once you age out of this stage, if you adapt to the TAO of life, you will face a greater risk of injury and ending your practice. Some cling tightly to the glory of practice and competition at great expense to their bodies. This is sad because the TAO changes as time goes on and martial arts practice can be across a lifespan. I can still be rigorous but you need to go with the flow and follow the way.

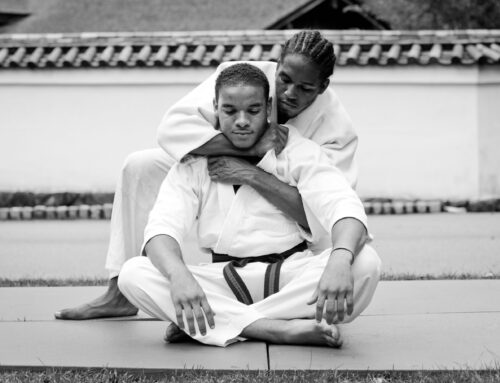

I subscribe to this philosophy. I created Zhang Sah’s program model to support martial arts practice across a person’s entire lifespan. Our Pre-MA and Shoshin sections are designed to build capacities and develop skills that are generalized and transferable to other activities that are not just for martial arts. As students advance and grow , we enter into the phase where competing is healthy for both mind and body, provided the skills and capacities needed were previously developed. A student can stay in this teen budo section for a good amount of time and enjoy being competitive if they choose. Ultimately, the student progresses into full adulthood and if they stick to the practice they can become very proficient in Budo and even master themselves through it. Beyond this point requires continued practice and accepting limits imposed by time as your body matures. This is the TAO, and it is not a weakness. Developing a meekness in your practice can ensure longevity. It is not glorious, but there can be happiness ever after by adapting practice in alignment with TAO.